Obama Celebrates the Anniversary of the ACA. Doctors React.

Doctors don't own the pen caps. Hospital executives do.

Note: in an earlier version of this article, I suggested that the Mayo Clinic’s patients were mostly not on Medicare. Dr. Anish Koka noted that it would be more accurate to say that commercial insurers subsidize the Medicare patients cared for by Mayo physicians. I changed the text to reflect this.

Fifteen years ago—on March 23, 2010—former president Barack Obama signed the Affordable Care Act into law. This week, he posted a short video on X marking its anniversary.

“It can feel like a different era sometimes,” Obama began. The video was not very long on substance—for example, Obama highlighted the fact that nearly 50 million Americans are now covered by the ACA, without examining how many employers had dropped their health-care coverage as a result of the law and thus compelled people to buy coverage through the government.

The video also offered no substantive comparison of health outcomes or affordability before and after the ACA. Obama presented the highly controversial law as a starting point toward further “progress,” but nonetheless an unmitigated success and obvious cause for celebration. He assured viewers that Obamacare’s success was not “just because of [him], but because Americans of all ages, all across the country, had the courage to speak up.”

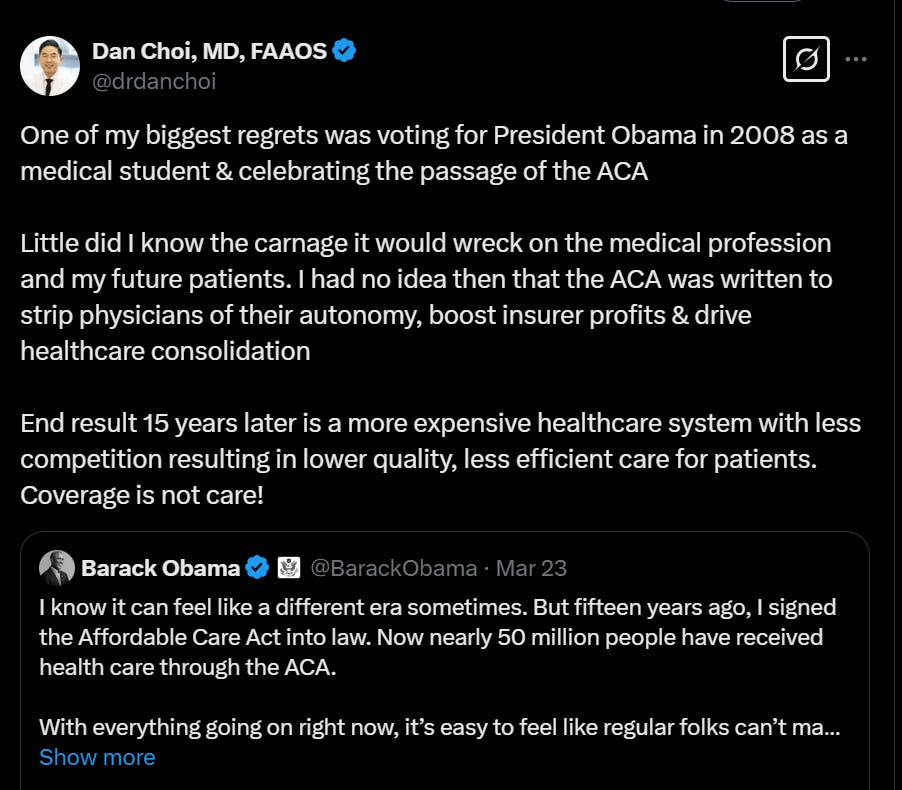

Perhaps taking this as a challenge, a grassroots collection of doctors quickly fired back at Obama on X, pointing to higher costs and diminished quality and outcomes for patients since the law’s passage. They also objected to the worsened working conditions for doctors that appeared to have been deliberately ushered in by the ACA. Spinal surgeon Dr. Dan Choi posted this note, which was shared by Elon Musk and viewed over 48 million times:

In an X space on March 24, a group of physicians came together to discuss Obama’s video and their own experiences of the ACA’s 15-year legacy. They urgently emphasized the multifaceted transformation of the medical profession itself into a corporatized and consolidated monolith.

One young doctor, John Paul Kolcun, lamented that nearly all his peers are employees rather than independent doctors, and so the “institutional memory” of a culture that relied on physician autonomy and authority is on the wane. His parents are now patients, he explained, and they remember a time when they had relatively straightforward access to independent physicians whom they knew well and with whom they had built a rapport over time. Now, they are often arbitrarily assigned to physician assistants or hospitalists at large facilities. Kolcun’s lack of exposure to a less mechanistic and more personal approach to medicine deformed his own training, he argued. Rather than being immediately answerable to patients, many doctors are primarily answerable to hospital administrators, insurers, teams of corporate vice presidents.

As the healthcare entrepreneur Dutch Rojas noted on X, “Through CMS, Medicare reimburses more for services rendered in hospitals and HOPDS [hospital-based outpatient departments] than independent physician offices.” He went on: “Once nimble and patient-focused, private practices were absorbed by not-for-profit health systems looking to maximize revenue through arbitrage, not outcomes.” Between 2012 and 2022, the share of physicians working in private practice dropped from 60.1% to 46.7%, according to a recent report by the American Medical Association. Obama’s famous catchphrase, “If you like your doctor, you can keep your doctor,” turned out to be woefully false, as doctors are almost all employees now, assigned to patients by bureaucratic fiat; the longstanding personal relationships that once defined physician-patient connection have virtually disappeared.

Even in private practices that have survived the financial squeeze of the ACA, there are innumerable small pressures on physicians and patients. Choi noted that vast numbers of physicians are quitting clinical medicine as a result of, for example, insurance companies playing doctor. The ACA empowered insurers to wield policy tools like “prior authorization” to abruptly and unexpectedly deny coverage for serious surgeries or treatments for chronic illnesses. Choi reported having had to cancel surgeries due to last-minute insurer denials after patients had “planned their entire life and support system” around serious, long-awaited procedures. As Choi put it, “Sad!”

Just this week, a physician family member complained that one of his patients had been denied coverage for treatment of a chronic condition—a treatment he had relied on for years. The doctor was forced to present his case to an insurance company, pleading for the medical necessity of the treatment and insisting on its effectiveness. The resultant lengthy appeals process requires doctors to repeatedly implore insurers to accept their medical reasoning, which insurers can deny in spite of a doctor’s strong recommendation. Such cases entail physician work hours that are not spent on clinical care, but rather on frustrating, frequently exhausting bureaucratic battles–during which patients cannot access medicine or vital procedures.

In an insightful and lengthy thread on X, the cardiologist Anish Koka traced much of this back to a 2009 article published in the New Yorker, “The Cost Conundrum,” by the surgeon and Democratic political activist Atul Gawande. Gawande’s writings on medicine have been highly influential in shaping Democratic health-care policies–he held a leading position in Bill Clinton’s campaign while on leave from medical school, and later served in the Department of Health and Human Services during the Clinton administration, among other things.

I plan to write more fully about the legacy of the “Cost Conundrum” in a future post. To summarize in brief: Gawande writes with disdain about independent physicians he met in McAllen, Texas, particularly those who worked at a physician-owned hospital. He believed that they were “over-utilizing” Medicare—ordering large numbers of tests and procedures in pursuit of Medicare payments, rather than because they were in the best interests of patients. In Gawande’s words,

Health-care costs ultimately arise from the accumulation of individual decisions doctors make about which services and treatments to write an order for. The most expensive piece of medical equipment, as the saying goes, is a doctor’s pen. And, as a rule, hospital executives don’t own the pen caps. Doctors do.

On the flip side, Gawande writes reverentially of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, in which doctors are paid salaries and, in Gawande’s telling, seem to have unlimited time to spend with patients. The essay glamorizes the idea of the employee physician, of selfless doctors pooling their resources, making it seem like a socialized approach to medicine might solve everything. As in the quote above, he subtly nudges the reader toward the assumption that “hospital executives” are better suited toward making good decisions for patients.

The essay made waves when Koka was in medical school, and he bought into the vision fully. But as Koka notes, Gawande apparently never examined the payment mechanisms behind the Mayo Clinic’s excellence. And as it turned out, the Mayo Clinic physicians were largely paid by commercial insurers rather than Medicare.

Gawande later apologized for this glaring oversight in his attempt to meaningfully compare different medical approaches and payment frameworks. But the “Cost Conundrum” nonetheless deeply informed Obama’s approach—for one thing, the ACA banned physician-owned hospitals. There is a deep suspicion of and disdain for independent doctors baked into the law—as one physician noted online, large facilities are easier to control.

There is also disdain for and suspicion of the “regular folks” Obama praised in his video. Koka shared an old clip of Jonathan Gruber, one of the architects of the ACA, justifying the “tortured way” in which the law was written. “Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage,” he explained, “and basically, call it the stupidity of the American voter or whatever, but that was really critical to get anything to pass. I wish. . . we could make it all transparent, but I’d rather have this law than not.”

In a separate clip, he explained his strategy as a “very clever, basic exploitation of the lack of economic understanding of the American voter.” This “exploitation,” he said, allowed the ACA’s architects to fraudulently present the bill as if it would tax insurers at no downstream cost to taxpayers, and as if young and healthy people would not have to pay exorbitant premiums. Multiple threads from Dr. Choi and others prove this to be the case–the ACA is not a cost-saving measure for most American patients.

Fifteen years on, by empowering corporations and inhibiting doctors and patients, the ACA has gone a long way toward transforming American medicine.